Spectroscopy

Spectroscopy was originally the study of the interaction between radiation and matter as a function of wavelength (λ). Historically, spectroscopy referred to the use of visible light dispersed according to its wavelength, e.g. by a prism. Later the concept was expanded greatly to comprise any measurement of a quantity as a function of either wavelength or frequency. Thus, it also can refer to a response to an alternating field or varying frequency (ν). A further extension of the scope of the definition added energy (E) as a variable, once the very close relationship E = hν for photons was realized (h is the Planck constant). A plot of the response as a function of wavelength—or more commonly frequency—is referred to as a spectrum; see also spectral linewidth.

Spectrometry is the spectroscopic technique used to assess the concentration or amount of a given chemical (atomic, molecular, or ionic) species. In this case, the instrument that performs such measurements is a spectrometer, spectrophotometer, or spectrograph.

Spectroscopy/spectrometry is often used in physical and analytical chemistry for the identification of substances through the spectrum emitted from or absorbed by them.

Spectroscopy/spectrometry is also heavily used in astronomy and remote sensing. Most large telescopes have spectrometers, which are used either to measure the chemical composition and physical properties of astronomical objects or to measure their velocities from the Doppler shift of their spectral lines.

Contents |

Classification of methods

Nature of excitation measured

The type of spectroscopy depends on the physical quantity measured. Normally, the quantity that is measured is an intensity, of energy either absorbed or produced.

- Electromagnetic spectroscopy involves interactions of matter with electromagnetic radiation, such as light.

- Electron spectroscopy involves interactions with electron beams. Auger spectroscopy involves inducing the Auger effect with an electron beam. In this case the measurement typically involves the kinetic energy of the electron as variable.

- Acoustic spectroscopy involves the frequency of sound.

- Dielectric spectroscopy involves the frequency of an external electrical field

- Mechanical spectroscopy involves the frequency of an external mechanical stress, e.g. a torsion applied to a piece of material.

Measurement process

Most spectroscopic methods are differentiated as either atomic or molecular based on whether or not they apply to atoms or molecules. Along with that distinction, they can be classified on the nature of their interaction:

- Absorption spectroscopy uses the range of the electromagnetic spectra in which a substance absorbs. This includes atomic absorption spectroscopy and various molecular techniques, such as infrared, ultraviolet-visible and microwave spectroscopy.

- Emission spectroscopy uses the range of electromagnetic spectra in which a substance radiates (emits). The substance first must absorb energy. This energy can be from a variety of sources, which determines the name of the subsequent emission, like luminescence. Molecular luminescence techniques include spectrofluorimetry.

- Scattering spectroscopy measures the amount of light that a substance scatters at certain wavelengths, incident angles, and polarization angles. One of the most useful applications of light scattering spectroscopy is Raman spectroscopy.

Common types

Absorption

Absorption spectroscopy is a technique in which the power of a beam of light measured before and after interaction with a sample is compared. Specific absorption techniques tend to be referred to by the wavelength of radiation measured such as ultraviolet, infrared or microwave absorption spectroscopy. Absorption occurs when the energy of the photons matches the energy difference between two states of the material.

Fluorescence

Fluorescence spectroscopy uses higher energy photons to excite a sample, which will then emit lower energy photons. This technique has become popular for its biochemical and medical applications, and can be used for confocal microscopy, fluorescence resonance energy transfer, and fluorescence lifetime imaging.

X-ray

When X-rays of sufficient frequency (energy) interact with a substance, inner shell electrons in the atom are excited to outer empty orbitals, or they may be removed completely, ionizing the atom. The inner shell "hole" will then be filled by electrons from outer orbitals. The energy available in this de-excitation process is emitted as radiation (fluorescence) or will remove other less-bound electrons from the atom (Auger effect). The absorption or emission frequencies (energies) are characteristic of the specific atom. In addition, for a specific atom, small frequency (energy) variations that are characteristic of the chemical bonding occur. With a suitable apparatus, these characteristic X-ray frequencies or Auger electron energies can be measured. X-ray absorption and emission spectroscopy is used in chemistry and material sciences to determine elemental composition and chemical bonding.

X-ray crystallography is a scattering process; crystalline materials scatter X-rays at well-defined angles. If the wavelength of the incident X-rays is known, this allows calculation of the distances between planes of atoms within the crystal. The intensities of the scattered X-rays give information about the atomic positions and allow the arrangement of the atoms within the crystal structure to be calculated. However, the X-ray light is then not dispersed according to its wavelength, which is set at a given value, and X-ray diffraction is thus not a spectroscopy.

Flame

Liquid solution samples are aspirated into a burner or nebulizer/burner combination, desolvated, atomized, and sometimes excited to a higher energy electronic state. The use of a flame during analysis requires fuel and oxidant, typically in the form of gases. Common fuel gases used are acetylene (ethyne) or hydrogen. Common oxidant gases used are oxygen, air, or nitrous oxide. These methods are often capable of analyzing metallic element analytes in the part per million, billion, or possibly lower concentration ranges. Light detectors are needed to detect light with the analysis information coming from the flame.

- Atomic Emission Spectroscopy - This method uses flame excitation; atoms are excited from the heat of the flame to emit light. This method commonly uses a total consumption burner with a round burning outlet. A higher temperature flame than atomic absorption spectroscopy (AA) is typically used to produce excitation of analyte atoms. Since analyte atoms are excited by the heat of the flame, no special elemental lamps to shine into the flame are needed. A high resolution polychromator can be used to produce an emission intensity vs. wavelength spectrum over a range of wavelengths showing multiple element excitation lines, meaning multiple elements can be detected in one run. Alternatively, a monochromator can be set at one wavelength to concentrate on analysis of a single element at a certain emission line. Plasma emission spectroscopy is a more modern version of this method. See Flame emission spectroscopy for more details.

- Atomic absorption spectroscopy (often called AA) - This method commonly uses a pre-burner nebulizer (or nebulizing chamber) to create a sample mist and a slot-shaped burner that gives a longer pathlength flame. The temperature of the flame is low enough that the flame itself does not excite sample atoms from their ground state. The nebulizer and flame are used to desolvate and atomize the sample, but the excitation of the analyte atoms is done by the use of lamps shining through the flame at various wavelengths for each type of analyte. In AA, the amount of light absorbed after going through the flame determines the amount of analyte in the sample. A graphite furnace for heating the sample to desolvate and atomize is commonly used for greater sensitivity. The graphite furnace method can also analyze some solid or slurry samples. Because of its good sensitivity and selectivity, it is still a commonly used method of analysis for certain trace elements in aqueous (and other liquid) samples.

- Atomic Fluorescence Spectroscopy - This method commonly uses a burner with a round burning outlet. The flame is used to solvate and atomize the sample, but a lamp shines light at a specific wavelength into the flame to excite the analyte atoms in the flame. The atoms of certain elements can then fluoresce emitting light in a different direction. The intensity of this fluorescing light is used for quantifying the amount of analyte element in the sample. A graphite furnace can also be used for atomic fluorescence spectroscopy. This method is not as commonly used as atomic absorption or plasma emission spectroscopy.

Plasma Emission Spectroscopy In some ways similar to flame atomic emission spectroscopy, it has largely replaced it.

- Direct-current plasma (DCP)

A direct-current plasma (DCP) is created by an electrical discharge between two electrodes. A plasma support gas is necessary, and Ar is common. Samples can be deposited on one of the electrodes, or if conducting can make up one electrode.

- Glow discharge-optical emission spectrometry (GD-OES)

- Inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES)

- Laser Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) (LIBS), also called Laser-induced plasma spectrometry (LIPS)

- Microwave-induced plasma (MIP)

Spark or arc (emission) spectroscopy - is used for the analysis of metallic elements in solid samples. For non-conductive materials, a sample is ground with graphite powder to make it conductive. In traditional arc spectroscopy methods, a sample of the solid was commonly ground up and destroyed during analysis. An electric arc or spark is passed through the sample, heating the sample to a high temperature to excite the atoms in it. The excited analyte atoms glow, emitting light at various wavelengths that could be detected by common spectroscopic methods. Since the conditions producing the arc emission typically are not controlled quantitatively, the analysis for the elements is qualitative. Nowadays, the spark sources with controlled discharges under an argon atmosphere allow that this method can be considered eminently quantitative, and its use is widely expanded worldwide through production control laboratories of foundries and steel mills.

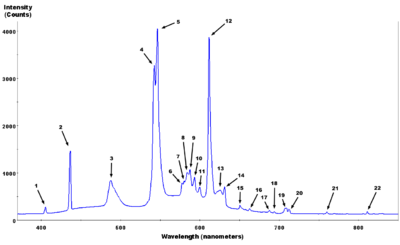

Visible

Many atoms emit or absorb visible light. In order to obtain a fine line spectrum, the atoms must be in a gas phase. This means that the substance has to be vaporised. The spectrum is studied in absorption or emission. Visible absorption spectroscopy is often combined with UV absorption spectroscopy in UV/Vis spectroscopy. Although this form may be uncommon as the human eye is a similar indicator, it still proves useful when distinguishing colours.

Ultraviolet

All atoms absorb in the Ultraviolet (UV) region because these photons are energetic enough to excite outer electrons. If the frequency is high enough, photoionization takes place. UV spectroscopy is also used in quantifying protein and DNA concentration as well as the ratio of protein to DNA concentration in a solution. Several amino acids usually found in protein, such as tryptophan, absorb light in the 280 nm range and DNA absorbs light in the 260 nm range. For this reason, the ratio of 260/280 nm absorbance is a good general indicator of the relative purity of a solution in terms of these two macromolecules. Reasonable estimates of protein or DNA concentration can also be made this way using Beer's law.

Infrared

Infrared spectroscopy offers the possibility to measure different types of inter atomic bond vibrations at different frequencies. Especially in organic chemistry the analysis of IR absorption spectra shows what type of bonds are present in the sample. It is also an important method for analysing polymers and constituents like fillers, pigments and plasticizers.

Near Infrared (NIR)

The near infrared NIR range, immediately beyond the visible wavelength range, is especially important for practical applications because of the much greater penetration depth of NIR radiation into the sample than in the case of mid IR spectroscopy range. This allows also large samples to be measured in each scan by NIR spectroscopy, and is currently employed for many practical applications such as: rapid grain analysis, medical diagnosis pharmaceuticals/medicines,[1] biotechnology, genomics analysis, proteomic analysis, interactomics research, inline textile monitoring, food analysis and chemical imaging/hyperspectral imaging of intact organisms,[2][3][4] plastics, textiles, insect detection, forensic lab application, crime detection and various military applications. Interpretation of Near-Infrared Spectra is important for chemical identification.[5]

Raman

Raman spectroscopy uses the inelastic scattering of light to analyse vibrational and rotational modes of molecules. The resulting 'fingerprints' are an aid to analysis.

Coherent anti-Stokes Raman spectroscopy (CARS)

CARS is a recent technique that has high sensitivity and powerful applications for in vivo spectroscopy and imaging.[6]

Nuclear magnetic resonance

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy analyzes the magnetic properties of certain atomic nuclei to determine different electronic local environments of hydrogen, carbon, or other atoms in an organic compound or other compound. This is used to help determine the structure of the compound.

Photoemission

Mössbauer

Transmission or conversion-electron (CEMS) modes of Mössbauer spectroscopy probe the properties of specific isotope nuclei in different atomic environments by analyzing the resonant absorption of characteristic energy gamma-rays known as the Mössbauer effect.

Other types

There are many different types of materials analysis techniques under the broad heading of "spectroscopy", utilizing a wide variety of different approaches to probing material properties, such as absorbance, reflection, emission, scattering, thermal conductivity, and refractive index.

- Acoustic spectroscopy

- Auger spectroscopy is a method used to study surfaces of materials on a micro-scale. It is often used in connection with electron microscopy.

- Cavity ring down spectroscopy

- Circular Dichroism spectroscopy

- Deep-level transient spectroscopy measures concentration and analyzes parameters of electrically active defects in semiconducting materials

- Dielectric spectroscopy

- Dual polarisation interferometry measures the real and imaginary components of the complex refractive index

- Force spectroscopy

- Fourier transform spectroscopy is an efficient method for processing spectra data obtained using interferometers. Nearly all infrared spectroscopy techniques (such as FTIR) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) are based on Fourier transforms.

- Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

- Hadron spectroscopy studies the energy/mass spectrum of hadrons according to spin, parity, and other particle properties. Baryon spectroscopy and meson spectroscopy are both types of hadron spectroscopy.

- Inelastic electron tunneling spectroscopy (IETS) uses the changes in current due to inelastic electron-vibration interaction at specific energies that can also measure optically forbidden transitions.

- Inelastic neutron scattering is similar to Raman spectroscopy, but uses neutrons instead of photons.

- Laser spectroscopy uses tunable lasers[7] and other types of coherent emission sources, such as optical parametric oscillators,[8] for selective excitation of atomic or molecular species.

- Ultra fast laser spectroscopy

- Mechanical spectroscopy involves interactions with macroscopic vibrations, such as phonons. An example is acoustic spectroscopy, involving sound waves.

- Neutron spin echo spectroscopy measures internal dynamics in proteins and other soft matter systems

- Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)

- Photoacoustic spectroscopy measures the sound waves produced upon the absorption of radiation.

- Photothermal spectroscopy measures heat evolved upon absorption of radiation.

- Raman optical activity spectroscopy exploits Raman scattering and optical activity effects to reveal detailed information on chiral centers in molecules.

- Terahertz spectroscopy uses wavelengths above infrared spectroscopy and below microwave or millimeter wave measurements.

- Time-resolved spectroscopy is the spectroscopy of matter in situations where the properties are changing with time.

- Thermal infrared spectroscopy measures thermal radiation emitted from materials and surfaces and is used to determine the type of bonds present in a sample as well as their lattice environment. The techniques are widely used by organic chemists, mineralogists, and planetary scientists.

Background subtraction

Background subtraction is a term typically used in spectroscopy when one explains the process of acquiring a background radiation level (or ambient radiation level) and then makes an algorithmic adjustment to the data to obtain qualitative information about any deviations from the background, even when they are an order of magnitude less decipherable than the background itself.

Background subtraction can affect a number of statistical calculations (Continuum, Compton, Bremsstrahlung) leading to improved overall system performance.

Applications

- Estimate weathered wood exposure times using Near infrared spectroscopy.[9]

- Cure monitoring of composites using Optical fibers

See also

- Absorption cross section

- Applied spectroscopy

- Astronomical spectroscopy

- Atomic spectroscopy

- Nuclear magnetic resonance

- 2D-FT NMRI and Spectroscopy

- 2D correlation analysis

- Near infrared spectroscopy

- Coherent spectroscopy

- Cold vapour atomic fluorescence spectroscopy

- Deep-level transient spectroscopy

- EPR spectroscopy

- Gamma spectroscopy

- Kelvin probe force microscope

- Metamerism (color)

- Rigid rotor

- Rotational spectroscopy

- Saturated spectroscopy

- Scanning tunneling spectroscopy

- Scattering theory

- Spectral power distributions

- Spectral reflectance

- Spectrophotometry

- Spectroscopic notation

- Spectrum analysis

- The Unscrambler (CAMO Software)

- Vibrational spectroscopy

- Vibrational circular dichroism spectroscopy

- Robert Bunsen

- Gustav Kirchhoff

- Joseph von Fraunhofer

References

- ↑ J. Dubois, G. Sando, E. N. Lewis, Near-Infrared Chemical Imaging, A Valuable Tool for the Pharmaceutical Industry, G.I.T. Laboratory Journal Europe, No. 1-2, 2007

- ↑ [http://www.malvern.com/LabEng/products/sdi/bibliography/sdi_bibliography.htm E. N. Lewis, E. Lee and L. H. Kidder, Combining Imaging and Spectroscopy: Solving Problems with Near-Infrared Chemical Imaging. Microscopy Today, Volume 12, No. 6, 11/2004.

- ↑ Near Infrared Microspectroscopy, Fluorescence Microspectroscopy,Infrared Chemical Imaging and High Resolution Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Analysis of Soybean Seeds, Somatic Embryos and Single Cells., Baianu, I.C. et al. 2004., In Oil Extraction and Analysis., D. Luthria, Editor pp.241-273, AOCS Press., Champaign, IL.

- ↑ Single Cancer Cell Detection by Near Infrared Microspectroscopy, Infrared Chemical Imaging and Fluorescence Microspectroscopy.2004.I. C. Baianu, D. Costescu, N. E. Hofmann and S. S. Korban, q-bio/0407006 (July 2004)

- ↑ J. Workman and L. Weyer, Practical Guide to Interpretive Near-Infrared Spectroscopy, © CRC – Taylor and Francis, Boca Raton, FL, English version 2007. ISBN: 1-57444-784-X

- ↑ C.L. Evans and X.S. Xie.2008. Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering Microscopy: Chemical Imaging for Biology and Medicine., doi:10.1146/annurev.anchem.1.031207.112754 Annual Review of Analytical Chemistry, 1: 883-909.

- ↑ W. Demtröder, Laser Spectroscopy, 3rd Ed. (Springer, 2003).

- ↑ F. J. Duarte (Ed.),Tunable Laser Applications, 2nd Ed. (CRC, 2009) Chapter 2.

- ↑ "Using NIR Spectroscopy to Predict Weathered Wood Exposure Times". http://www.fpl.fs.fed.us/documnts/pdf2006/fpl_2006_wang002.pdf.

External links

- Spectroscopy links at the Open Directory Project

- Amateur spectroscopy links at the Open Directory Project

- Timeline of Spectroscopy

- Chemometric Analysis for Spectroscopy

- The Science of Spectroscopy - supported by NASA, includes OpenSpectrum, a Wiki-based learning tool for spectroscopy that anyone can edit

- A Short Study of the Characteristics of two Lab Spectroscopes

- NIST government spectroscopy data

- Potentiodynamic Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||